Tarmo Saks: an Estonian born abroad - part of two worlds

There are nearly 200 000 Estonians living abroad- some were born there, some have moved there, and some were forced to leave Estonia at one time or another. Everyone has their own story. This is just one of them.

There were times growing up when it was a bit embarrassing (or at least awkward) being a väliseestlane (an Estonian from abroad) – in both Canada and Estonia. I sometimes felt like a child of two different worlds.

It all started on my very first day of kindergarten in Toronto when my teacher had to call my mother and ask her to bring me home because I was crying constantly and could barely speak or understand English.

Years later for a multicultural food day at school when we were asked to bring an ethnic dish to share with other classmates my parents toiled all night to make rosolje (a classic Estonian salad made of beets, potatoes, herring and a lot of other ingredients). I assumed they were going to make pirukad (meat pies / dumplings) that everyone would certainly enjoy. I was so embarrassed at the pink and fishy concoction that rosolje is (although I now think it is delicious), that when I took it to school the next morning, I did not even put it on the table with the other food dishes my classmates brought, but left it in my locker – where it stayed for months festering in its own juices. Of course I told my parents everyone loved the rosolje and didn’t tell them the true story until nearly a decade later.

And then there were the questions: What kind of name is Tarmo? What is Estonia? Where is Estonia? Is Estonia a real country or are you just making that up?

In Estonia, there was a different sort of embarrassment. The first time I went to Estonia was in 1990 for the Song and Dance Festival where as part of the Toronto folk dancing group Kungla we had to perform in front of over 10000 people at Kalev Stadium as part of a combined väliseesti folk dance group that included Estonians from Canada, USA, Sweden and Australia. It was a simple folk dance and we basically just had to stay in a circular pattern – but it ended up being more amoeba-like. We got a nice ovation and applause from the crowd, but probably because we were an odd curiosity, we tried our best, and they were surprised/questioning who are these people and why we were even there.

Väliseestlased (well, me and my friends) at the Lenin statue in Tallinn right after the end of Laulupidu 1990 (July 1st 1990)

And then there were also the questions: You have a weird accent, where are you from? If you were born in Canada, how can you speak Estonian? Why are you here?

To this day (and now living in Estonia) if I go to a store, restaurant, or bar and order something they will still sometimes reply to me in Finnish because of my peculiar accent – that really irks me.

But, despite some of these awkard and embarrassing moments, I was always proud to be Estonian. I felt kind of special and that I had a purpose being in Canada. My parents always told me growing up that the Estonian language and culture has to persevere and because Estonia was occupied by the Soviet Union at the time, we, the Estonians abroad (or in exile), were possibly the last hope for the Estonian people.

At times I felt like I lived some sort of a double superhero life in Canada. During the day I would be at normal school. During the evening I would be at the Estonian House attending Estonian school, taking part in folk dancing, and helping to preserve Estonian culture when the entire world had abandoned us.

A generation in exile

My grandparents (and father and aunt) were among the nearly 80 000 Estonians who had to flee Estonia in the fateful autman of 1944 (known as the Suurpõgenemine).

My grandfather on my father's side was a Forest Brother. His brother had already been arrested by the NKVD in 1941 and died two years later in a Soviet GULAG camp. My father was only 10 years old at the time when they had to flee Estonia in 1944.

My grandfather on my mother’s side volunteered and fought on the eastern front in an Estonian battalion of the German Army near Leningrad (now Saint Petersburg), which became one of the most brutal battles of the Second World War. In the autumn of 1944 he finally had to tell his platoon of soldiers that for now Estonia was lost and that he did not want his yet unborn daughter to grow up in a Soviet-occupied Estonia. My mother was born a month later in Finland in October 1944..

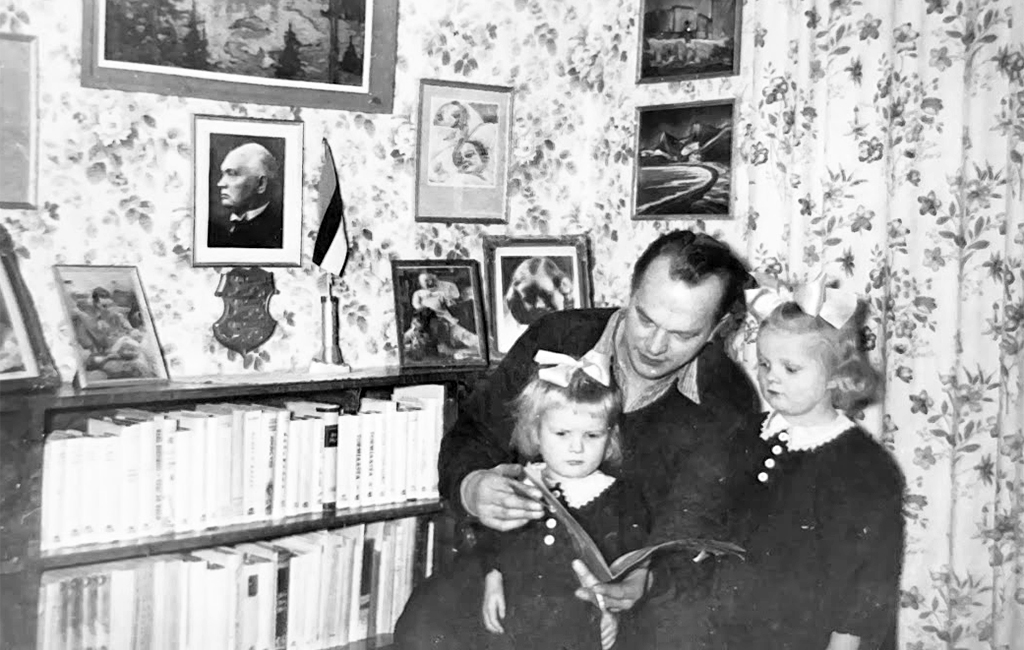

My grandparents both continued the struggle to preserve Estonian culture in exile in their own ways.

My grandfather (Edgar Valter Saks) was the founder and editor of the first weekly newspaper for Estonians abroad in Sweden, appropriately called Välis-Eesti, in 1944. In Canada he was the founder of several Estonian organizations and served as the Minister of Education for the Estonian government in exile. He also wrote several books about Estonian history - that have some and unique and interesting theories.

My other grandfather (Aksel Tamme) helped build the Jõekääru summer camp north of Toronto in the early 1950’s for Estonian children and was a member of EKKT (Eesti Kunstnike Koondis Torontos). His unique art adorns the walls of many homes across North America and in Estonian community buildings like Jöekääru, Seedrioru, Ehatare and the Lakewood Estonian House in New Jersey.

My grandfather probably trying to teach Estonian history to my aunt and mother (right) (1949?)

The torch of preserving Estonian culture in Canada was then passed to my parents as it was in so many families abroad. The stark and sad reality that Estonia was going to be occupied for a very long time was already clear.

My mother (Anne-Marie Saks) became a teacher at the Estonian House in Toronto and was camp director at Jõekaaru for several years where she was affectionaitely known as ‘Tädi Anne’.

Anne-Marie Saks - Jõekääru camp juhataja (1990)

My father (Ants Saks) was part of a group that helped rejuvenate and grow Korporatsioon Vironia (an Estonian academic organization) in Toronto and instilled in his three sons a patriotic pride in being Estonian. We always knew Isa was on his way home because we could often hear him blaring the Song Festival song Kodumaa from blocks away at full volume and windows open from his car stereo system- the entire neighbourhood could hear.

Vironia 100 anniversary in Toronto (2000) - Madis Saks, Ants Saks, Tarmo Saks, Markus Saks

Coming back to Estonia

By the time I was in high school I was no longer embarrassed to be Estonian. Estonia was making international headlines (with the Baltic Way in 1989, the re-adoption of the Estonian flag in 1990, and of course the restoration of independence in 1991). My friends, acquaintances, and teachers were very curious about these events and I was now more than happy to talk and explain to them what was going on.

But when I wasn’t in high school, most of my time was still spent with my Estonian friends and being a part of the Estonian community. And after going to Estonia for the first time in 1990, I kept thinking of when I could go back again.

And so I did. In 1996 for ESTO 96 (the Estonian World Festival in Stockholm and Tallinn) and then in 2004 and 2009 for the Song and Dance Festival. My friends and I rarely ventured outside of Tallinn during those times so in 2011 I decided to come back during a non-song festival year and actually travel all around Estonia. I didn’t realize that 2011 was also a festival year – this time the Youth Song and Dance Festival that ended up being as big and emotional as the main song and dance festivals. But I did see Estonia that year and decided to move to Estonia the next year.

I could never acticulate or properly explain why I wanted to move to Estonia. I still can’t. It was just something that I had to do and my family and friends somehow understood that.

But, after moving to Estonia I still continued to be part of two worlds. For years afterward I spent nearly half the year in Canada to be with my parents, family and friends. I would usually leave Estonia right after Midsummer's Day (Jaanipäev) spend a few months in Canada, come back to Estonia, and then go back to Canada again for Christmas and New Year’s and come back to Estonia right before Estonian Independence Day in February. Of course if it was a Song and Dance Festival year, like 2014, I would stay in Estonia longer because my friends and family would be coming to Estonia.

First time at a Song Festival with one of my brothers. I'm crying. (2014)

A purpose - globalestonian.com

But, after moving to Estonia, there were times when I would think, is living in Estonia enough? Am I contributing to the preservation of Estonian culture by just being here? My grandparents and parents had helped preserve Estonian culture abroad, but what can my role (however small) be now that Estonia is independent and I am living here? I thought of joining the Estonian Defence League (Kaitseliit) several times, but was in Canada so often I couldn't make the commitment.

It was then that my good friend Marcus Kolga asked me if I wanted to help him with the globalestonian.com portal in 2017. It was an idea Marcus and fellow Toronto-Estonian Toomas Kütti had conceived of many years before and was a website that brought together news and events from Estonain communities from around the world and that would answer the simple questions: Where are we? What are we doing? The end-goal Marcus had was to gift the portal to the Estonian state as part of the EV100 program (which happened in 2019).

And so I finally had a purpose. I could live in Estonia and contribute to the worldwide Estonian community at the same time. Being part of two worlds and being a väliseestlane in Estonia now made sense.

To make things even better a job opportunity opened at the Integration Foundation to continue managing and developing the globalestonian.com portal- and that is what I continue to do to this day. The Ministry of Culture and the Foreign Ministry have been integral in the further development of the portal and we encourage anyone interested to join the new “globalestonian.com sõbrad” program.

Still part of two worlds

Even though I now permanently live in Estonia and have a job that I enjoy and believe has an important purpose, I am still a part of two worlds. Although my brother and his family just recently moved to Estonia, most of my family and friends live in Canada and I don’t get to visit them as often as I once did.

And I still get the same questions here: You have a weird accent, where are you from? If you were born in Canada, how can you speak Estonian? Why are you here? But at least people don’t respond to me in Finnish as often as they once did.

My grandparents did not live long enough to see Estonia become independent.

My parents sadly never got to visit an independent Estonia.

But I know that they are all looking down and are proud that all they fought for and all the effort to preserve Estonian culture and eestlus abroad was worth it.

And I hope that doing my very small part also makes them proud.

Tarmo Saks

globalestonian.com administrator (Integration Foundation)

Estonian born in Canada