Experts: Variety in diaspora speech shows Estonian language is alive and well

Just like learners of other languages, heritage language speakers need support and encouragement, not to have their language anxiety stoked. The variety in Estonian as a heritage language, meanwhile, is actually indicative of the endurance of the Estonian language itself, find University of Tartu (TÜ) linguists Mari-Liis Korkus, Adele Vaks and Virve Vihman in an article that first appeared in the magazine "Oma Keel."

Researchers are becoming increasingly interested in the varieties of languages spoken abroad, leading to the increasing use of the term heritage language, or pärandkeel. In Estonia, however, this term is relatively new and used rarely. In this article, we compare heritage language with other similar concepts, describe characteristics of Estonian as a heritage language and also introduce what heritage languages are spoken in Estonia.

Introduction to the terminology

The term heritage language, or pärandkeel, refers to a home language that differs from the societal language and which a child thus learns based on limited input. The boundaries of this concept are at times blurred, as various forms of bilingualism overlap and it isn't possible in every individual case to unequivocally say whether someone is a heritage speaker or not.

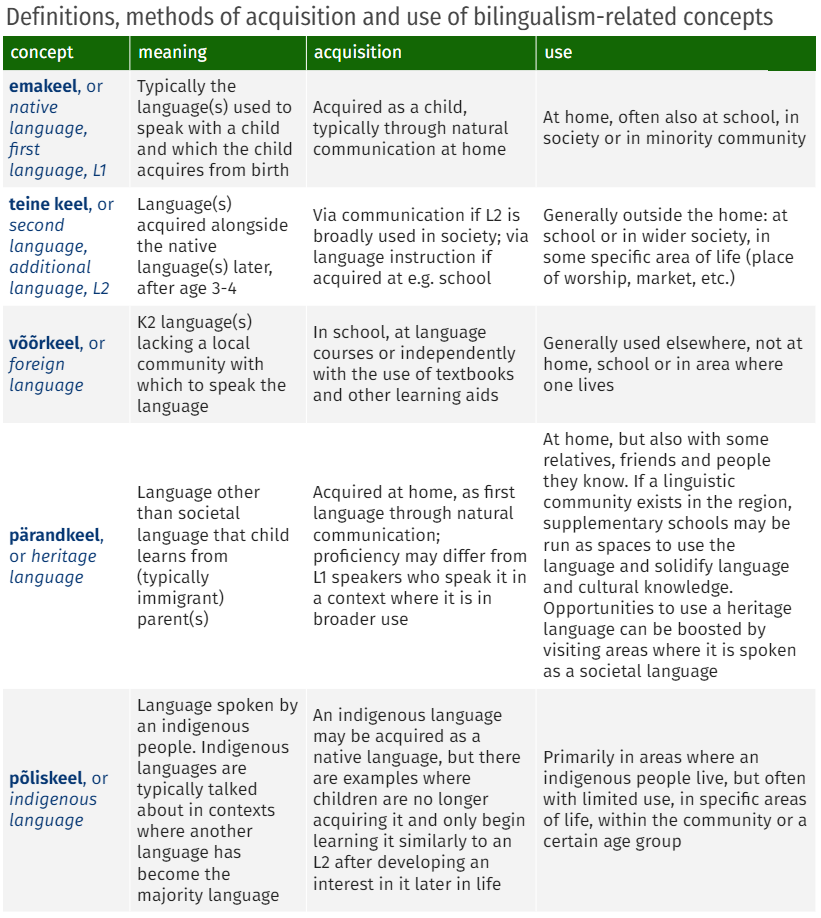

The following chart compares various concepts related to bilingualism, which differ in terms of language acquisition and/or use, including the concept of heritage language.

More comprehensive information about concepts and studies related to bilingualism can be found in a 2021 Estonian-language review of the literature by Reili Argus et al (link to PDF).

Estonian as a heritage language

A typical example of Estonian as a heritage language is that of väliseestlased, or diaspora Estonians. To illustrate, we'll use the Canadian-born 40-year-old Uku Michael as an example. He acquired Estonian as his native language, or emakeel, from his parents, and English as well once he started kindergarten.

Uku Michael's Estonian differs from those of his peers in Estonia. As he has acquired the language from a more limited circle of speakers, his vocabulary may reflect words from his parents' generation no longer in use by young people in Estonia; moreover, his vocabulary is more limited than that of his peers. English, which has been used by Uku Michael alongside Estonian for most of his life, plays its own part as well: we can pick up on the English-influenced pronunciation of the letter R in his speech, and perhaps the more frequent use of the passive voice has found its way into his Estonian (e.g. "Olin koolis kiusatud," meaning "I was bullied in school"), which is entirely grammatical, just much less common in Estonia [as opposed to the active "Mind kiusati koolis"].

Each variant of Estonian as a heritage language has its own distinguishing features, influenced by the societal language(s) with which Estonian is in contact as well as what generation the speakers are.

The Estonian-born Emma, who moved to Norway with her parents at one year old and who picked up Norwegian when she started attending kindergarten there, speaks Estonian a bit differently than her parents do, who moved away from Estonia as adults. Should Emma herself start a family in Norway as an adult, then her children's Estonian will differ in turn from her own. Should Emma's grandchildren also grow up in Norway, they may no longer speak Estonian.

American linguist Joshua Fishman described the stages of heritage language shift within communities with the three-generation model: immigrants arrive speaking their native language, their children grow up bilingual and grandchildren already only speaking the language of their new homeland. The heritage language is no longer needed in everyday life, and even within the family, they talk in the majority language.

Even so, Fishman already noted that national identity is often more long-lived than language: a third-generation Norwegian Estonian may not speak the Estonian language, but still feel connected to Estonia.

Such trends, however, do not constitute absolute rules: if Emma or Uku Michael's grandchildren visit their great-aunt in Estonia every summer, chat with relatives their age in Estonia on Snapchat and attend the Song Festival with their Estonian choir from Toronto or Stavanger, then they have plenty of reasons and opportunities to speak Estonian.

To that end, motivation – both kindling and sustaining it – is also partly in the hands of Estonians back in Estonia: studies show that with each passing generation, heritage language speakers experience increasing language anxiety around relatives in their home country because they feel like they don't speak the language "well enough."

If we encourage and support the learning and use of Estonian even when it sounds a bit different, we become one variety of language richer and open up opportunities for new generations of heritage language speakers to forge a stronger connection with their Estonian identity.

In the words of Ellen Valter, general manager of the KESKUS International Estonian Center project in Toronto, "We out here who still speak Estonian – with mistakes maybe – but in our hearts we're Estonians."

Read More (opens in new tab)